The Loves of João Max César Monteiro de Deus

20/07/2024

- Y. Z.

20/07/2024

- Y. Z.

João César Monteiro seems to be a filmmaker keen on filming life. But the golden rule of this seventh art form is that life is completely removed from cinema and cinema is completely removed from life. How to reconcile cinema with life? Or, how to see life through cinema? A Comédia de Deus (1995) is the decisive attempt to break the rule, to connect the two together, perhaps to reach life through cinema, through “pure perversion”, as Carmelo Bene puts it. What Monteiro proves, in A Comédia de Deus, is the inherent attachment of puerility to perversion, and of perversion to freedom, both in person and in camera.

The most striking feature of A Comédia de Deus is undoubtedly that of the comedy of language, precisely what the Marx brothers and Leo McCarey achieved in 1932 with their Duck Soup. Duck soup, God’s comedy. The American ice-cream, made by adding corn starch and gelatin to a base of cream, as a perfume, taste as smell, the conflict between two senses. The taste of cinema history. Even though cinema is fraud, there are no lies in A Comédia de Deus, only what is unsaid. Anything that comes out of João de Deus’ mouth is funny, the same way it was with Rufus Firefly. This gesture of predictability, of bundling up all the quips that the Portuguese language offers, makes the spectator complicit, conscious in their discovery of each joke. It is vulgar, but not provocative. The indecency seems inherent. In the same way, there is never a clarification on whether Paraiso do Gelado is an ice-cream shop or a brothel. It’s certainly shot like one. The duplicity of things!

So how does A Comédia de Deus approximate life? The employment of Lumière-isms that unravels the distanciation between João César Monteiro the director and Max Monteiro the actor. To go back to life it is necessary to go back to the first filmmakers who crossed the threshold of life into the cinema. The effect: a strong rhythm between all of the actors in the frame, all their movements exposed and amplified in the childlike gaze of the camera. Not childlike in its innocence, but in its perversion upon contact with adulthood. In the scene where João de Deus reads his dignified “manifesto” of the ice cream, all the miniscule interactions of each of the characters (or the lack thereof) are brought to the surface, with the effect that the space each occupies is registered clearly, subsequently allowing for any and all variations of action to take place. Manifesto against the church, against established order, even that of a gustatory order.

What is also implied by the lack of complex camera setups for different camera angles – Monteiro acknowledges the feeling of putting the direction of the film down while he is on screen as “fantastic” – is the fact that not everything has meaning. Emphasis is given to the natural development of two actors in the frame. When one looks back upon the old greats: Ford, Sirk, Walsh, one gets the feeling that every minimal movement of the characters within the frame-stage, every movement across geometrical shapes within the space changes the identity of each character. All of this is thrown out of the window.

This is not just some random declaration of abandoning control of the camera in order for it to capture “life”. This is not how life is captured. The space is a tightly controlled one, so tightly controlled, in fact, that all of its mysteries can only be discovered through the personality of João de Deus. He is putting himself on display for her.

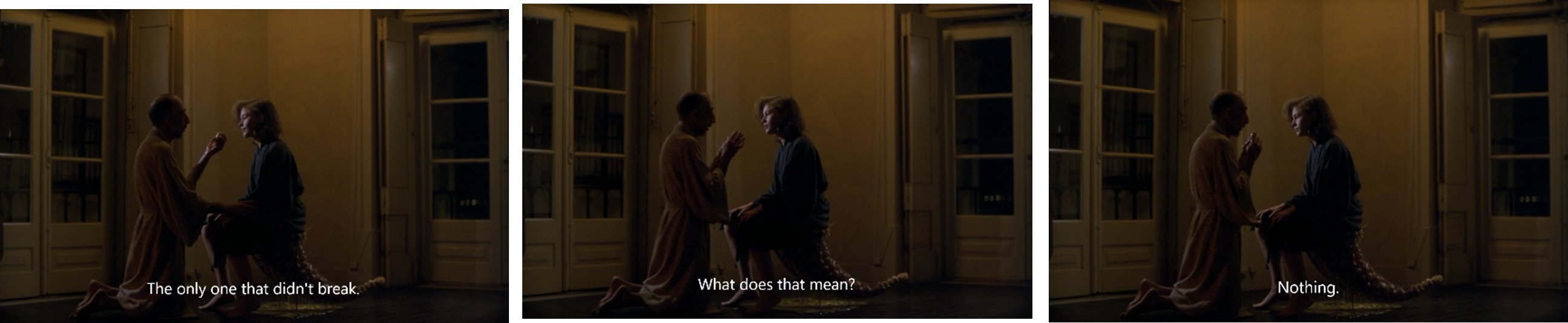

According to Monteiro, João de Deus never speaks a single swear word in the film, only “little words”, “palavrinhas”. But there are also little actions: for example, jumping like a sly animal in order to approach Joaninha in the bathtub, and doing a full stretch and cracking his feet before opening the door for Judite in the middle of the night. Something must be pointed out about the cracking: after this scene, cracking of knuckles was heard in the theatre, undoubtedly in response to João de Deus. His action has been directly transferred to the spectator. What does this mean? Nothing. However, there is a definite connection between the film and the spectator at this point. João de Deus’ cinematic ego is never allowed to overtake his physical existence, because his whole body is taken care of by the camera. One gets a sense of a naturalistic struggle, a sexual pervert trying to make a living in the world.

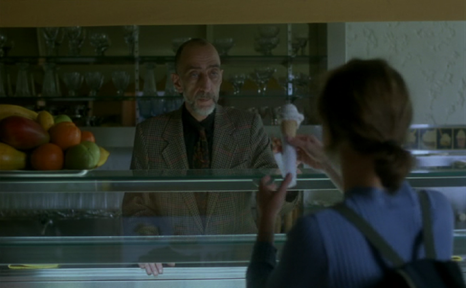

These gestures also backfire, and in fact end up being the downfall of João de Deus. In fact, when he first meets Joaninha in the shop, and she walks into the frame into his gaze, the paper wrapped around the ice cream cone unravels. This sudden change in rhythm from the slow delivery of both of the actors signals something that has just come into play, something that is unstoppable. Difficult to say whether this is “the ultimate perversion”, although one is certain that the 14-year-old daughter of the butcher is João de Deus’ downfall, the femme fatale.

One gets the feeling that the end starts after this encounter. Besides the general anticlerical themes that can be found throughout the entire film, there is also an interesting play on masculinity/femininity, to the point where, once João puts on Joaninha’s underwear on a whim (another “little” action, although a decisive one), there is an androgyny that seems to derive from the “pure perversion” that Carmelo Bene described. Notice the whimsical nature of the sequence, childlike and immature, set over a classical piece, with the portrait of Serge Daney in the background. For the first time, João de Deus isn’t aware of his behavior, he is out of his depth.

A two-minute-long static shot shows João’s meeting with the butcher in the aftermath. This time, his conscious behavior is rejected, as all of his cigarettes are slapped to the ground. It is supposed to be a comedic sequence, although there is a very clear sadness beneath the surface.

In fact, João de Deus’ identity is systematically dismantled, to the point that there is no more room left for him in the film. His ice cream shop is taken away from him:

And the artwork which documents his existence is burned (the equivalence of the Book of Thoughts to celluloid must not be disregarded. This is when the spectator understand that the exploits of João de Deus are based on his love):

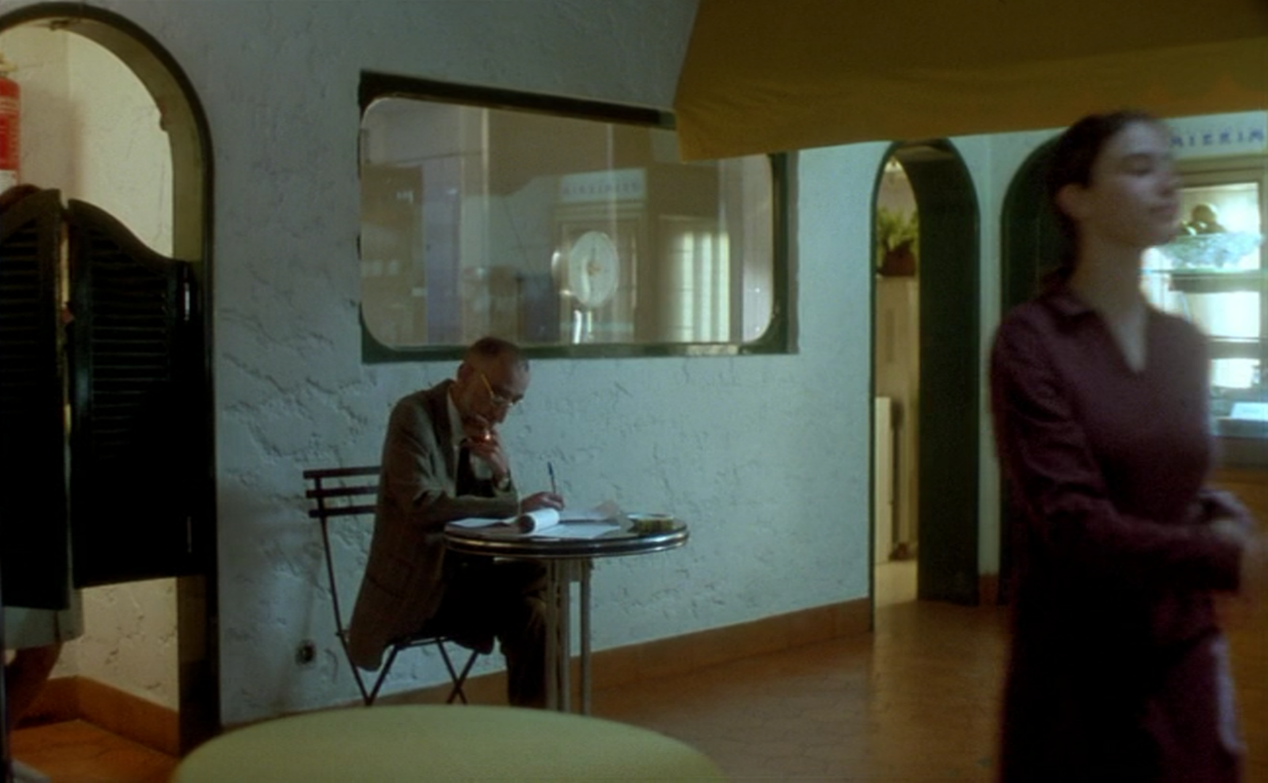

It is the filmmaker who produces the distaste now, anachronous in status:

The downing strike into life. All that remains of the film is a handprint left by an unknown individual – authorship, but from who? The pigeons of Lisbon now feast on disintegration.