Showgirls (1995): Brecht, Ford, and Mirror Images

07/11/2024

- Nomi

07/11/2024

- Nomi

Within Showgirls, Paul Verhoeven tends not just towards Brechtian devices of epic theater but more explicitly towards devices of Ford’s own application of epic theater, which, as Jean-Marie Straub puts, is “more Brecht than Brecht.” Through the establishment of mirror images, Verhoeven is able to constantly reestablish motifs and images in contrast—myth versus reality—and through this relationship, he is able to posit every element of the film (as in the greatest of Ford pictures) in dialectic relationship with every other element: sound against image, edit against composition, narrative against character, spectacle against reality, gesture against expression. It is through these dialectical relationships of image and sound that Verhoeven is able to draw out so many dialectical relationships of various aspects of the American myth, specifically the mythology of Vegas, and it is here (through his distinctly European lens) that he manages to dismantle every aspect of violent, lurid, spectacular absurdity present within said myth.

Now, briefly as an aside, I would like to contradict some aspects of critique and praise commonly ascribed to Showgirls that do not represent the actuality of the film, that being the label of Showgirls as an erotic film and as exploitation. Although certainly about eroticism—to an obsessive level even—the film is far from actively erotic, each sexual gesture more venomous than lurid. Although initially the film seems to play into an erotic structure and appeal, eventually every notably erotic element becomes eroded by the machine-like structure and minutia of repeated performance at the film's core. The establishment of rhythm—along with Verhoeven’s careful, delicate mise en scène—converts the representation of the sexual into analysis of transaction, objectification, and wars of power. Each lurid dance, from the most simple to the most complex, becomes representative of a battle of minds and ambitions as much as it does physical, tangible bodies; dances represent conflict, bodies violently clash against one another, and what is Showgirls defined by if not the clash of and distance between bodies? The other label here—even more absurd than the previous—of exploitation, is a total misnomer. The heightened tone here is not a means of idol spectacle but the exact opposite; a means of interrogating the American myth of Vegas, of self-actualization, and of the image of the geographical celebrity on its own level. The heightened tone as well as the films' interplay with camp culture—a culture of not just heightened dramatics but of explicit queerness, both of which the film operates on the basis of—are both a means of achieving this mythological tapestry. Furthermore, every sexual and physical expression within is a means of representing some dialectic between two persons and the attributes which inform them (along the lines of sexuality, race, gender, power, class, consent/bodily autonomy, and culture, of course all represented through a rampantly materialist lens), meaning not once does the films' emphasis on the physical—on sex and sexuality—relegate it to the category eroticism or exploitation.

Showgirls most simply operates via the abstraction of traditional narrative and theatrical convention (in the sense of Brecht) and through the emphasis on embellishment between mirror images. Every image crafted here has its counterimage, every thesis its antithesis, and this mirrored structure plays just as much into the literal mise en scène of the film as it does into the form. As well, in the Fordian sense, Showgirls is primed not just with dialectical, materialist genius but also with immense poetic value, specifically with the poetics present in space and gesture, and most aptly with the difference between two persons and the difference between one’s performed gestures and self (something most-common in every Ford picture).

It is in the iconography of mirrors that Showgirls routinely reveals itself; mirror images not just between two scenes but as literal props; it is in front of mirrors (a classical piece of mise en scène, which can also be observed routinely in Ford’s work that myths and identities are constructed routinely over and over, only to be immediately performed (always in context of their previous construction)) where one can observe, time and time again, identities being constructed, formed, and warped.

Another motif of Ford’s cinema can be observed in the opening car pan as the car drives by the camera, most notably similar to that of Fort Apache, a film Showgirls will go on to share images with (in fact, explicit mirror images and comparable Brechtian devices). Both are used not just to emphasize the speed of travel, as our protagonists careen towards unknown environments that will shatter their perspectives (and in some cases take their lives), but also to show the degree which environment dwarves the protagonists, as the vistas of both Las Vegas and Fort Apache’s Arizona takes over the shot as their various means of travel (Car and Wagon) fade into the distance.

Three shots demonstrating Ford’s panning technique applied to a traveling wagon in Fort Apache

A tracking shot applied to a car mirroring Ford’s own in Showgirls

It is the space of performers, not of the audience, by which Showgirls can routinely be observed placed within. Although often cutting back to a wide view of a stage performance, relegating us to the audiences' perspective for but a moment, the film is often interested in placing us, along with Nomi, on the stage, associating us more closely with the performers, and focusing more on the specific interactions of various gestures and facial expressions that occur in the midst of these gladiatorial bouts for power and commerce, which, inevitably given the film’s machine-like structure, become less spectacular as they buckle under the minutiae of repetition. Also, important to note is the use of Steadicam, a means of tracing the motion of performers’ gestures while also emphasizing the stillness of the camera along a set axis, allowing those gestures to be hyper-scrutinized without a particular mode of spatial embellishment (here along the vertical plane).

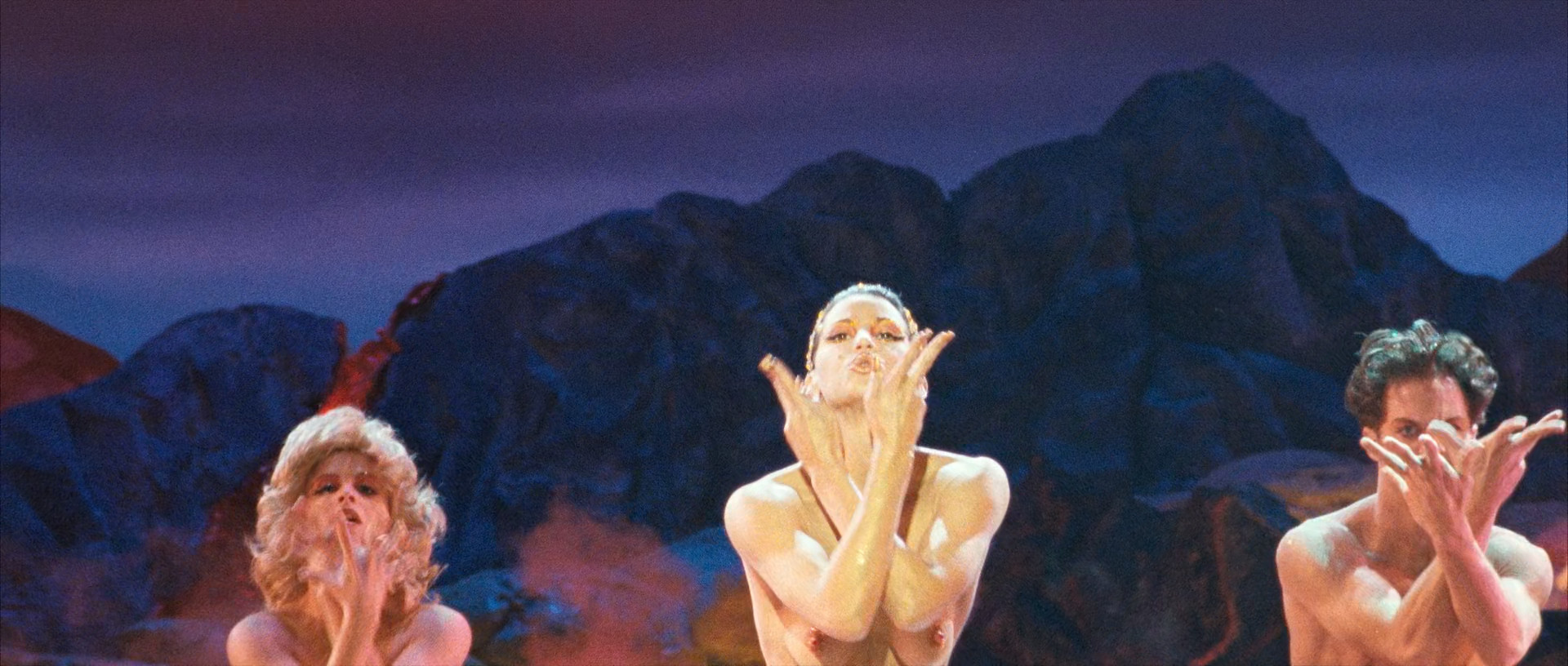

From Nomi’s perspective, we first see the spectacle of Vegas, and of the first Goddess performance play out. This is the only time she is relegated to the role of spectator in regard to the Goddess performances, and truly the only time in the film we bear witness to this grand performance as voyeur in isolation (aside from cutbacks to Nomi’s own reaction). It should not be surprising, then, that this is where the myth of this performance as grand, spectacular, a means of Nomi achieving both a sense of self and ascending in both class and status, is first presented, and it should be no surprise that it is through the spatial distance between performer and voyeur that this myth is able to be sustained (of course, only so long as new participants in the myth, new voyeurs, are drawn towards it). Let us also not forget what Nomi does while witnessing—not just observe, but mirror, and with it begins the embellishment of the self, or performance.

Nomi seeing and mirroring a dance at her first Goddess show in Showgirls

A technique drawn from Ford is the emphasis on complex dialogues, in which multiple characters speak, observe, gesture, and play off each other in a way that does not make itself necessarily accessible for a first-time viewer. Of course, the most notable of these scenes being the aforementioned scenes of grand Goddess performances; these could be explored ad nauseam for their rich complexity in character and mise en scène, however I’d like to focus on a more specific example: a lap dance early in the film with multiple moving parts, motivations, and wars of power. In this scene, possibly one of the most singularly complex of the film, we have multiple distinct wars of power, complex gazes, gestures, and shifting participants. To begin with, we have three major participants, Nomi, unwilling but forced into the role of performer by her boss Al—someone with tangible influence who is now relegated outside the margins of the screen, a minor participant in terms of physical imposition over compositions and space—Zack, at first seeming timid, submissive, at the whims of Cristal (later revealed to be the true source of power and oppression by the films contexts), and Cristal, the current lead member of the Goddess cast, who appears in-power but really is no more in-power than any other performer at the Goddess, who in paying Nomi is attempting to humiliate her (having already compared Nomi’s work to prostitution, of which Nomi takes immense offense to). Through this dance, the context of power, the line between the “submissive” Zack (the true holder of capital and thus of power), the voyeur Cristal, who both intends to humiliate Nomi and has her own role and power embellished by Nomi’s active role in the performance, and Nomi, forced into the dance as her body is reduced to an object of capital and her ability to consent diminished by the nature of her labor, who wields her physicality and the gestures present in the dance itself to blur the lines of power established by Cristal (and in-part, unknowably by Zack) constantly shifts not just with dialogue but with the positioning of actors and their expressions. It’s significant to note, even further, that Nomi does not just perform for Zack (of who is the only participant she physically touches during the performance), but even more so to Cristal, the voyeur; the glances between these two, performer and voyeur, are where the real weight of the scene is held, and thus, where the weight of both physical intimacy, body as material object and capital, and where the weight of the distance between persons, their expressions (physical and emotional), and gestures is established even further as a mode of establishing and retaining power. Constantly through gestures and distance, performance is crafted, constantly reconstructed, embellished, and handled, for example, Cristal must not only humiliate Nomi, but most do so in front of Zack, feeling threatened by Nomi’s youth, of which will become increasingly apparent throughout the film. This is not even to mention James, the bouncer whom Nomi befriends—and whose relationship is further blurred by his own manipulative role towards Nomi, also involving dialectic observations on the intersections between race, class, sex, gender, and capital—who is made voyeur even further along the margins of the space. Further complicating this scene is its counter-image, the intensely physical sex scene in the pool closer to the end of the film, in which Nomi mirrors her exact motions during the lap dance (and in which her body is even further reduced to a sort of capital, of which she is even further unaware of). One could compare the complexity of this scene to any number of Fordian conversations, where characters speak over one another, constantly perform different roles, and represent different ideals and systems, but most comparable is a scene from Ford’s greatest picture, The Long Gray Line, a dinner scene that establishes a series of mirror images, shifting roles, and complex interactions within the margins of a set space (the delicate positioning of actors within said space most important of all).

The lap dance scene, and it’s mirror image in the pool from Showgirls

The dinner scene in The Long Gray Line

A simpler comparative image establishing Verhoeven’s relationship to Ford is between Showgirls and Fort Apache, that being the contrast between Nomi’s initial audition for the Goddess show and a scene in which sergeants in Fort Apache take over a drill for newer recruits. Both relegate actors on screen to one of two functions, those not-in-power, forced into similar assemblages of lines, and those in-power, going down a line, testing each of those not-in-power one by one, mocking them. Along both these spatial lines in each film, participants not-in-power must perform for those above them and must reinforce their status based on necessary factors they either have or have-not (in the case of Showgirls, this is an unknown “IT factor,”, some sexual magnetism made physical, and in Fort Apache, it has to do with their birthplace (the Irish generals seeking Irish recruits)). Although both emulate the appearance of seeking knowledge or expertise, it is truly order and an inherent gift they seek; not skill but the reinforcement of pre-existing culture and myth. As is so common in Ford—and as occurs in this exact scene in Fort Apache—comedy is used to establish tension, drama, and tragedy. The mocking gestures of both the man tasked with weeding out those with the unnamed gift of performance in Showgirls and of the sergeants testing recruits in Fort Apache are of immense weight of tragedy, cruel mockery disguised as comedy being used to establish order, people being demeaned as an act of violent restriction and cultural hegemony.

The audition for Goddess in Showgirls

The drill sergeants testing recruits in Fort Apache

Another example of two scenes in explicit dialectic contrast is one scene between Nomi and Molly at the beginning of the film, and another between Nomi and Cristal later in: two people eating, discussing their social roles, their past, and future in each, although the two meetings (both of which Nomi is invited to rather than dictating) could not be more distinct. It is in this meeting with Molly that Nomi is most ungated, until the very end of the film. It is the only time in which she strips her layers of performance, and presents only herself to another person (Molly, throughout the film, being the only truly kind person to Nomi (her position as a working-class black woman, in this case, cannot be understated). This lack of performance is most visible when compared with the dinner scene, where Nomi and Cristal talk, much further in the film. Note the violent way Nomi sets down the ketchup bottle she so thoroughly exhausts in frustration while eating with Molly; contrast this with the composed way Cristal sips her wine while interacting with Nomi, while Nomi never takes a drink. Between Nomi and Cristal, a violent power struggle is formed, with Cristal composed but targeting Nomi’s highly visible insecurities (labeling Nomi a “whore” an aforementioned label highly complex in its use throughout the film and more related to its cultural status than its material status in the eyes of Nomi throughout), while Nomi is totally put off balance; the idea that she could be “like Cristal” as Cristal suggests is here a matter of grave offense, but of course her taking on the gestures, expressions, and ideals of Cristal began as early as her witnessing Cristal first perform, which is the entire reason Cristal here must reassert her power through performing her status at any given moment the two share a space.

The first scene of Nomi and Molly eating and the second scene of Nomi and Cristal eating in Showgirls

It is not just in the Goddess performances by which performance, myth, and power are majorly established, but even more so in the dressing room, a maze of mirrors where identities are first constructed, melded, and constantly pitted against each other. In these scenes, each one preceding a dance (both at the Cheetah where Nomi first works as a stripper and the Goddess), we see the performers take on costumes, roles in which they perform on-stage, and outfits in which they battle against each other in a violent show of power. Note the initial image of Nomi first entering the changing room, a name explicitly being stripped from her new mirror to make room for her own. In making note of this unknown person’s replacement, Verhoeven necessarily invokes the exchangeability of performers in the Goddess show. Possibly, the image with the most weight in the entire film is the image of Cristal establishing herself over Nomi’s mirror (Nomi’s mirror, here, reflecting Cristal) and the image just preceding the show which follows, pushing Cristal down their stairs, mirroring not just her actions but supplanting her role, taking on her position of (false) power, and becoming her.

Nomi’s mirror being set up and Cristal positioning herself over Nomi’s mirror in Showgirls

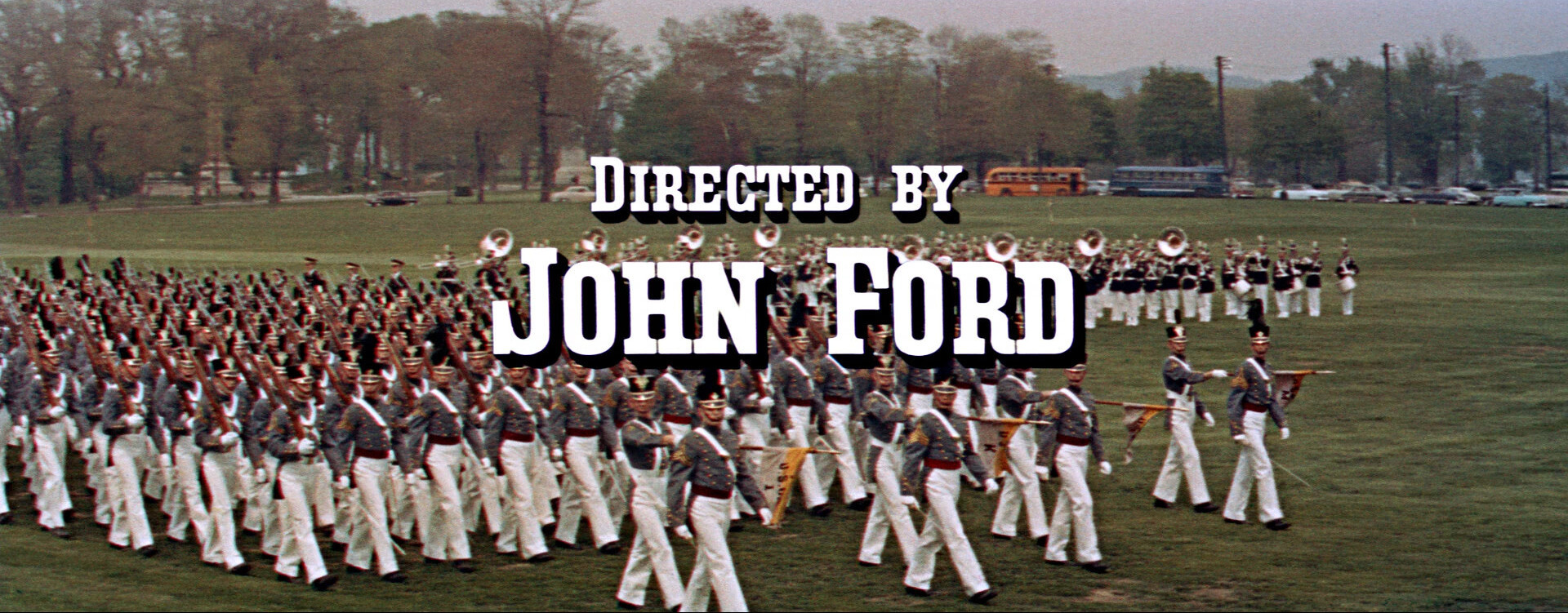

In this examination of the interchangeability of performers and the machine-like rhythm between scenes of the dressing room and of performances, Showgirls establishes its greatest direct relationship with the structure of a Ford film, that being The Long Gray Line (the film that Jean-Marie Straub infamously labeled “experimental” in structure, which applies no less to Showgirls). The Long Gray Line, also obsessed with the constant performance of various social roles and the dialectics drawn between the intersections of various genders, races, and classes in an attempt to gain (highly internal) power, and even more so obsessed with the interchangeability of persons surrounding a protagonist (note the way in which war’s shift in The Long Gray Line versus the shifting Goddess shows in Showgirls, both have ever-shifting goals, with ever-shifting participants constantly seeking different forms of power, both of which always value the same traditions and idolize the same structure). Both The Long Gray Line and Showgirls analyze spaces caught in ideological, spatial, and mythological stasis. Protagonists who both shift from keen-eyed, young, ambitious people with nowhere else to go and no foreknowledge of the culture by which they involve themselves to people reinforcing and benefiting the same structure that previously (and will continue to) oppressed them. Even further comparable is the establishment of mirror images and the gradient shift of tone mirrored between both—both structurally shift from comic structures to highly tragic and complex portraits where previously comic images become re-coded as tragic (such as Marty’s young and old self both reacting to the master of the sword, initially bewildered than furious at the modern youth’s own bewilderment)—and the seemingly endless minutia of repetition present in both the culture of Vegas and West Point. Of course, one massive schism between the two is that Nomi is able to exit just at the point of no return, rejecting the contradiction built up at the core of her identity throughout. Although constantly seeking a similar exit, Marty is not so lucky and remains forever a participant in the culture that claimed his identity. As the long gray line marches on, so too does the Goddess show, always the same in geography and culture, always distinct in participants and chronology; and what is the March of the Troops if not a dance, a mass group of people mirroring the same motions as people watch in awe, also so distinctly orchestrated by music?

Marty’s shocked reaction to first hearing the title of Master of the Sword, versus his shocked reaction in his older age to hearing the same title mocked in The Long Gray Line

A Parade in The Long Gray Line and a Goddess Performance in Showgirls

Even further demonstrating this replicability of performers—and this relationship between Nomi’s and Cristal’s identities—is the exact mirror image presented between Nomi’s and Cristal’s introduction to the greater public as the new respective lead performers of the Goddess show (note Verhoeven’s explicit inclusion that Cristal is not a long-term lead of the show, but rather just begins as lead with the film’s own beginning, just having replaced another performer). Note the exactness of words in each of their respective introductions; although they’re labeled celebrity BEYOND celebrity, they’re both intrinsically tied to a specific time and place, a specific chronology and geography; they’re both doomed to obscurity as their time on the stage comes to an end, no doubt being hoisted out of power by someone just as hungry for it as they once were; power that this new person will soon come to find is no doubt false in status, and yet they will continue to risk everything to maintain.

Cristal first being introduced as the lead of Goddess versus Nomi in the same position in Showgirls

As is noted in Tag Gallagher's, in Quotation of Jean-Marie Straub John Ford: Multiple Perspectives (Costa, Comolli, Gallagher, Straub):

“McBride analyzes Fort Apache in this light, pointing out how Captain York donning Colonel Thursday’s hat at the end is a Brechtian device [like the cardinal donning the Pope’s robes in Brecht’s Galileo] ...”

It is, in nearly the exact same sense, that Showgirls invokes its most Fordian device—or even more aptly—it’s most Brechtian device yet. As Nomi dons Cristal’s hat, she accepts the contradiction in her identity (and so to is this acceptance signaled in a kiss between the two, so eagerly denied up til now); she is both obsessively and exactly formed of and by the same context that Cristal is. When Cristal states, “You and me, we’re exactly alike,” and Nomi replies, “mmm, mmm” shaking her head dismissively, it is a statement both correct and incorrect; Nomi the icon is exactly like Cristal, yet what Nomi inevitably becomes by the end of the film is the result of rejecting that status—said iconographic and mythological elements—as a means of sustaining this new self. If Cristal was once “someone younger” in the quote, “There’s always someone younger and hungrier coming down the stairs after you” then so too is Nomi, and with this realization, Nomi must be left behind, and the person who once was Nomi must leave; the contradictions are too much to bear.

Cristal donning her own hat versus Nomi donning her hat towards the end of the film in Showgirls

Colonel Thursday donning his hat versus Captain York donning it towards the end of Fort Apache

Cristal tempting Nomi into a kiss in order to mock her, versus Nomi and Cristal kissing at the end of the film in Showgirls

Showgirls, inevitably, ends just like the greatest of Ford pictures; our lead, as Fordian hero, must leave the geographical, mythological, and spatial tapestry (here Vegas), which has up to this point informed her. The unbearable weight of contradictions becomes too much for the space of the film to bear. Polly Ann Costello (Nomi’s birth name), who we do not meet, is posited in dialectic contrast with Nomi Malone, who we see constructed as Idol throughout, and most Fordian of all the film posits the synthesis of these two identities; who we once knew as Nomi, who was once Polly, is now neither one of these two women nor both, but the synthesis of the two, of her past self and the self she formed in Vegas through continuous power struggle. Who she is now we cannot know, nor where she is going, and just like in many of Ford’s greatest works, she leaves just as she came; in Ford so often train, boat, horse, here by the same Hitchhiker she was introduced to the world by (the symbol of the Vegas vagabond, the Elvis hairdo is no coincidence here), and mirrored to is the road sign establishing an explicit beginning and end to the system of Las Vegas. Thus, with the film’s final mirror image, no appeasement is achieved.

Nomi hitchhiking at the start of the film versus two closing stills of the film in Showgirls

The beginning and end parade in The Long Gray Line