CINEMATECA PORTUGUESA-MUSEU DO CINEMA

JEAN-CLAUDE BIETTE - THE THEATRE OF THE MATTERS

8th and 10th of January 2025 - translation courtesy of Y. Z.

JEAN-CLAUDE BIETTE - THE THEATRE OF THE MATTERS

8th and 10th of January 2025 - translation courtesy of Y. Z.

SALTIMBANK / 2003

A film by Jean-Claude Biette

Saltimbank was the last film from Jean-Claude Biette, who died unexpectedly and suddenly (at 60 years old) in June 2003, and who never got to attend the commercial premiere of what had become the final title of his work. Biette defined himself in a very simple manner cinematographically: he was a “conteur”, a “teller1 of stories”. But, for someone like him, the act of “telling” flew above the very stories that were told. In all of Biette’s films, and Saltimbank is no exception, more than one story, there is a crossing of stories, and even more than a crossing of stories there is the frequent supposition of other stories beyond those that are told - it is, out of all the rest2, one of the points which makes Biette a “familiar” of Jacques Rivette, in whose cinema suspicions abound (the “complots”, real or hypothetical) of “hidden” stories in the interstices of the story that is narrated.

The idea of a “network3” (or of a “réseau”, like the French say) underlying the choice of the actors and collaborators of Biette, all of them coming “from before” and in some cases even from much before, is very important in the construction of Saltimbank. There is a story of family, to start: the Saltim family, whose activities and interests are divided between banking (the Saltimbank, lovely pun) and the theatre. And then, there is a way of drawing the narrative, or the narratives, which multiplies in characters and functions based on the connections between them, in the encounters and the disencounters4, in the presences and the absences. The pairs and the trios remake themselves from scene to scene, and the perfect “gag” is that scene in the restaurant where there are various characters who know each other and who we have already heard talking one about the other but who, we then realize, we have not yet seen together. It is at the same time totally artificial and totally naturalist, and this delicate equilibrium finds its crucial point in the environment in which everyone, in one way or another, moves, the theatre.

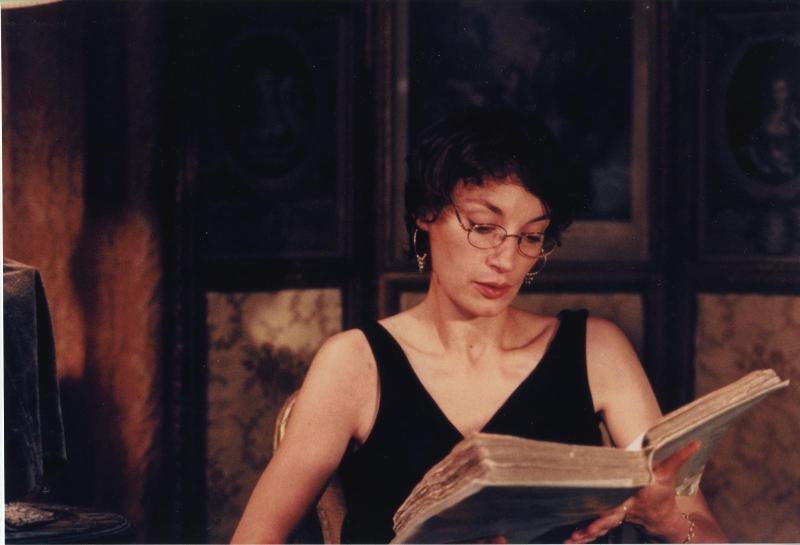

Even when it is “social theatre”, like in the scenes at the house of the Saltims’ matriarch (the veteran Micheline Presle), to whom Jeanne Balibar’s character will read texts of Voltaire. Or even a species of “professional theatre”: when the banker Saltim (Jean-Marc Barr) offers to Balibar a position in the direction of the bank, aren’t they exactly functions of representation that he proposes to her? Full of irony, and full of tenderness for all of its characters, be they seducers more or less cowards (the two Saltim brothers, Barr, the banker, and the magnificent Jean-Christophe Bouvet, the dilettante theatre enthusiast) or creators more or less complexed and anguished (the director of the theatre or Ana Maria, the director5), this shadow of an anguish pervades through Saltimbank, let us say very “modern”, the anguish of isolation, of incomprehension, of incommunication - and we would add “an anguish for the lack of a species of reflexion” when we remember that in Saltimbank Biette multiplies the mirrors (the first scene: Bouvet in the bathroom, doing his toilette) and some of the most beautiful scenes (like the dialogue between Balibar and the Berliner actor) take place before mirrors. And would it be a coincidence that in this visit of Balibar’s to Berlin that the character of Hanns Zischler emerges, who has the project of “connecting” the theatres of Berlin? Like “connecting” a world that has been “disconnected”? Transposed for the circuits of artistic creation (and particularly of theatre), and put into articulation with the circuits of finance represented by the Saltimbank, the question gives lots to chew on6, and we wouldn’t promise that it isn’t the central question of Saltimbank.

And “all this in an anodyne way, able to fool the spectator accustomed to the effects of cinema, to an escalation of dramatic tension that never occurs in Saltimbank, because ‘that nothing happens or that everything happens is indifferent’, like Nietzsche said, because events rarely have consequences…”. And after this passage stolen from the review of Saltimbank written by Jean-Baptiste Morain in the Inrockuptibles, a brilliant summary of what Biette films here and of the way in which he films it, let us watch the film.

Luís Miguel Oliveira.