HIGH NOON

by Glauber Rocha

10-11/01/1960 - translated from the Portuguese by Trixi

by Glauber Rocha

10-11/01/1960 - translated from the Portuguese by Trixi

Entering the analysis of the new western to say that the advent of the “new” lies in the bourgeoisification of the hero is to want to destroy the only great manifestation of American culture.

Bourgeoisie means reactionarism and the western is the only school of progressive films that exists. But since in these poor appendices the critic is mistaken, why then consider him as anything other than an observer who is pretentiously knowledgeable about cinema? Because, if he is knowledgeable, he is not following the fruit of his knowledge properly. He should revise his method and take an objective position which is the only correct one in any art criticism.

The new western was not a thematic renovation but a structural one. It was, within the Hollywood industrial complex, determined by economic reasons. The consequent superstructure was the new form. What within the economic origin of the new western must have suffered planning: the changing of the form, the adoption of the shock, the elimination of the fusions.

With the aim of reaching a new form of spectacle, new stories framed in a more psychological line of introspection that allows the camera to get closer to the character, hence the close-up-armed basis of the montage of High Noon.

Because if it wasn't for an artisan’s hand like Fred Zinnemann's, or any other like Delmer Daves', Anthony Mann's — to name two masters of the genre — or even ones like John Huston’s, Robert Aldrich’s and a few others who led the game of framing and cutting in Hollywood, Carl Foreman's story would perhaps be ridiculous.

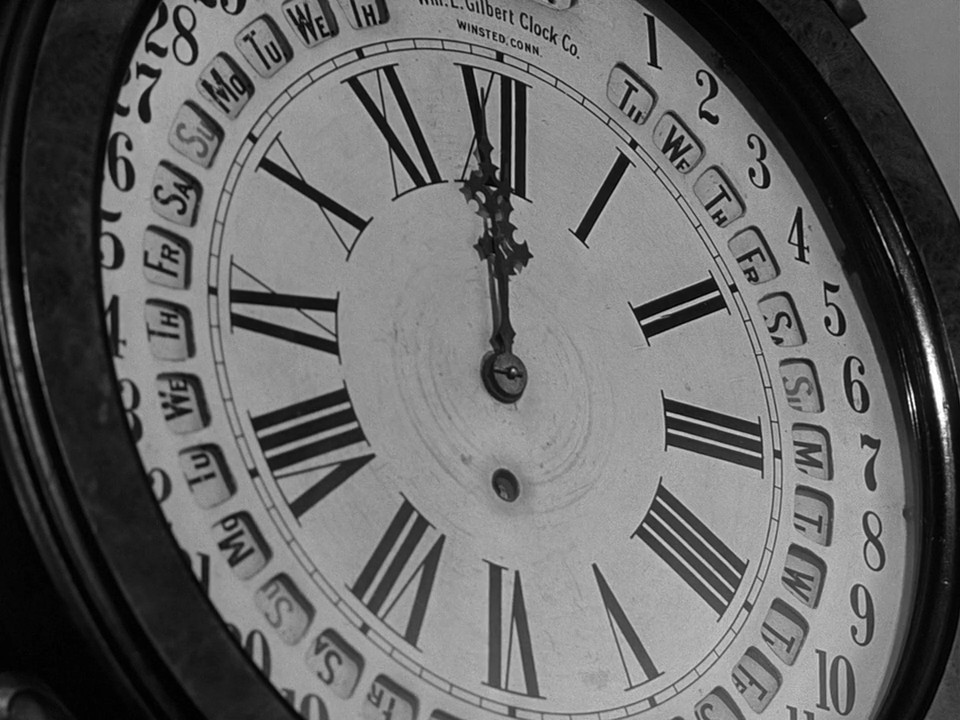

What makes High Noon a great movie is the dramatic construction, its rhythm corresponding to real time. The invention is not Zinnemann's. Robert Wise had previously brought us the classic The Set-Up. But Fred Zinnemann's exercise is of equal agility and oriented at building up the climax and introducing, with all the stylistic refinement, the new SHOCK in the western, which marked, at the moment when Frank Miller jumps into the station to kill Sheriff Will Kane with his three gunmen, the advent of the modern western.

It's in that unusual visual ambience — the gray plastic and the geometric frame — that the bandits are at the station waiting for the train. It’s in that dry course of time that Will Kane marches, asking for help from friend to friend. It’s in this work with time that Zinnemann directs the camera at this or that, counting, second by second of the frame, and giving the psychological conflict of reality — the same one that is established in the spectator's perception — an exact duration of the same trance of the character.

One makes a film of anything. Of a deserted beach. Of a single man. It's the camera that creates a movie, never a script on which the camera only registers delusions or literary-psychological transfigurations as in Fellini. Or in Bergman, who deforms the figure within the most irritating theatrical parnassianism in search of a “modernness” that only people trembling with sexual problems like and are delirious in front of. But delirious in the face of their own psychosis and not in the face of the film as a work of art. And thus, in the presence of Bergman, Fellini or Kazan, they would get irritated, as all lucid people do, electing Visconti as the filmic truth that is born from his exactitude, his testimony of man.

That's why it is irritating for a critic to call a hero bourgeois. Bourgeois is he who doesn't get rid of marginal contemplation and doesn't penetrate in the most beautiful verse of all the arts: the hot noon hour when a solitary and indignant man, although a believer in the values of courage and of defense and of revenge, draws his weapons as he would draw his pen or his brush, or his own blood and confronts four gunmen marching to kill him.

“Burguês não é o herói que saca a pistola e enfrenta a morte no quente meio-dia”. Diário de Notícias. Salvador, 10-11/1/1960, 3º Caderno, Suplemento de Artes e Letras. [Republished in O Século do Cinema, 2006]