Films of Age

03/09/2024

- Epnr

03/09/2024

- Epnr

The idea of American avant-garde film is saturated with the idea of young man’s films— films produced by 20-30 year old men at the height of 16mms availability in the 1960s and ‘70s. We can begin to define a young man's film by looking towards the work of Jack Smith, Ron Rice, Andrew Noren, or the earliest works of Stan Brakhage, and look to see how they are reactive in nature. Capturing everything they can with a sense of wonder and energy that— while beautiful— oftentimes never reflect and take the time to not only understand how the images inform the life they are going to live but how their own lives are imposing onto the images. Jerome Hiler, on the other hand, like the few other elderly avant-garde filmmakers (Robert Beavers, Ken Jacobs), reevaluates footage filmed in his youth. This relationship raises a question: How to discuss what could be described as old man’s films without falling into the pitfalls of contemporary auteurist ‘late style’ discourse? The invocation of ‘late style’ relies on vague gestures toward the films of so-called old masters, proclaiming their last few films as inherently unique and requiring a deeper understanding of their filmography, bastardising the purpose of auteurism, understanding that filmmakers work are in conversation with each other, and instead treating it as a direct progression towards their ‘best’ works. Through this focus on the final films the value of a filmmaker's earliest work is muddied and reduced to serving the purpose of contextualising their last. We can separate our definition of young or old man’s film by not defining it them in relation to each other but within their own terms. A young man’s film can be lacking in reflection, and an old man’s film may be coloured by it, but that condition does not beget the opposite in the other. We must think of death formally, as Adorno puts it;

“If, in the face of death's reality, art's rights lose their force, then the former will certainly not be able to be absorbed directly into the work in the guise of its "subject." Death is imposed only on created beings, not on works of art, and thus it has appeared in art only in a refracted mode, as allegory.” (Adorno, 2002)

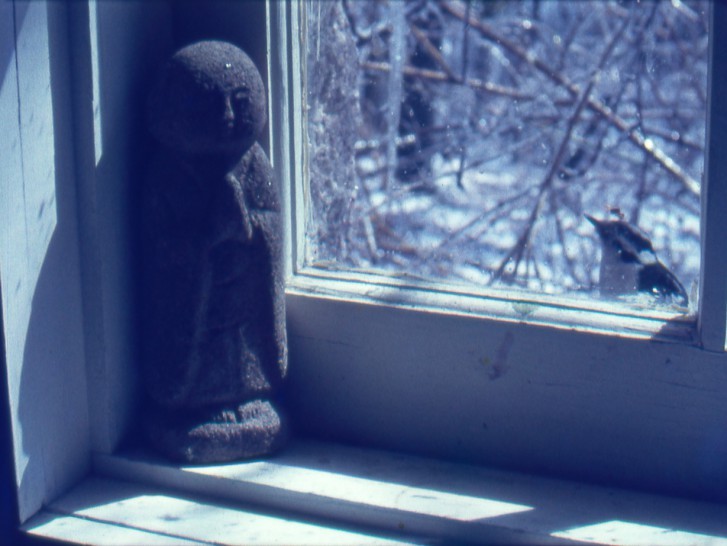

Death for the filmmaker does not exist in a young man’s film, yet it’s the central formal element in the old man’s film, the spectre of life imposes itself onto all the images. While this sounds distressing, the works of Hiler are some of the freest portraits of life. The depth of archival footage seems unending and almost all profound, begging to be constructed into the films that now exist. Not only is the footage itself aged, but so are the stocks on which its being captured, rephotographing with outdated Kodachrome to pull out specific textures and colours. In doing so, the material nature of film, that of being wound through a camera times over prior to being developed and printed, is found to be integral in how it relates to the memory that has been imposed.

Having been the primary projectionist for Andy Warhol's Chelsea Girls (1966), Hiler’s work, one that focuses so strongly on double exposure, is noticeably influenced by the practice of dual projection (which was developed through this experience). Even in Hiler’s exploration of stained glass windows (present in In the Stone House (2012), Ruling Star (2019), and his essay film Cinema Before 1300 (2023)), the influence of dual projection can be felt, as two stained glass windows can reflect into the same space. This may seem in opposition to the understanding of film as film, as it views film through the same lens as glass. However, we can see how it could be closer than claiming that they are wholly dissimilar; The fundamental process of film projection is one of light being shot through a ‘stained’ sheet of cellulose acetate or, in the past, nitrate film.

Hiler’s closeness to the New American Cinema group is apparent throughout all of his work, and this is no surprise given his proximity to Stan Brakhage, Andy Warhol, and Gregory J. Markopoulos. Striking resemblances to the editing rhythms of Markopoulos are present throughout most of his films, but are clearest during a sequence in In the Stone House, in which light reflects through shutters onto transparent curtains. This footage, not shot by Hiler but rather Nathaniel Dorsky, is treated with such care and precision in the edit. It calls to mind the way Markopoulos spoke of the filming and editing of Gammelion (1968)— “These two rolls of film will be used as if they were gold itself.” (Markopoulos, 2014) Through this process, the importance Hiler places on the footage used becomes clear, the images are a precious material.

With all this in mind, we can arrive at the central value of Hiler’s work, more so than its beauty or its importance in understanding avant-garde film; It is work of a medium on the brink of extinction. Film stocks are no longer being produced, labs are shutting down, cameras are reaching prohibitively expensive prices. The aged stocks Hiler uses are aesthetically pleasing, but also a necessity on some levels, as the preferred stocks are no longer available in any other form other than out of date. What was once an open field for experimentation and personal film has become forgotten and even more inaccessible than it ever was prior. Filmmakers like Hiler and their insistence on the medium of 16mm film are keeping alive one of the most important artistic traditions, that of the independent analogue film.