Howard Hawks and Hatari (1962)

18/08/2024

- Devin Leong

18/08/2024

- Devin Leong

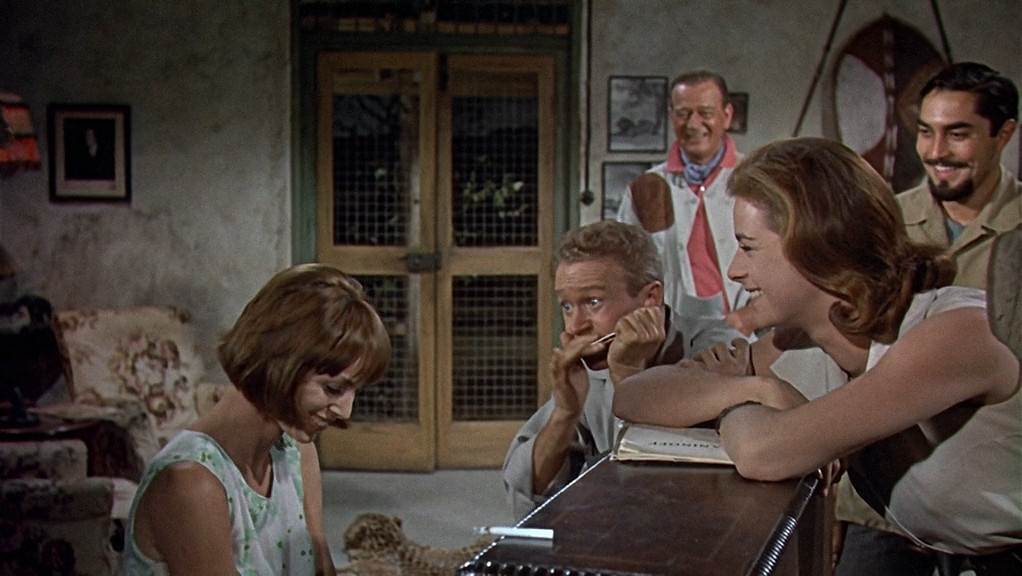

In thinking of ways to praise Hatari, one tries to come up with observations that do not apply verbatim to Rio Bravo. This is not as easy as it sounds, both are the best “Hawks hangout films”, with a reserved Wayne being the patriarch who falls in love at the center of the film. To discern what makes Hatari great, and especially representative of the beauty of Hawks, one must seek out the differences between his two best films up to this point. First and foremost, the film is not a western, no one is gunned down, there are no bandits or outlaws imposing upon our group. The only form of harm to the characters comes from failures in progressive attempts to capture a rhino. With this, the best traits of a Hawks film can show themselves casually. In Rio Bravo, there is grace between the bloodshed, a shared song between cowboys as they await a siege. Hatari contains a musical bonding scene as well, (in the first third of the film!) but whereas Nelson and Martin’s jailhouse duet is a triumph, it’s no different from any other scene in Hatari.

Robin Wood wrote that the creation of a Hawks film really lay in the collaboration of actors and cameras, not in preparation or in editing. “Thus the true significance of a Hawks film is not something that could exist on paper before shooting.” (Wood, 1983) His process is exemplified strongest here. Every movement and gesture feels organic, more intuitive than reality itself. Note the scene in which Pockets dances with Dallas. She leads him into the room, camera pans to the doorway, cut into the room, Brandy withdraws to the table while still dancing. One gets lost in Hawks’ rhythm, not a movement, action, or cut feels out of place.

Such elegance is kept even at the film’s most absurd, more absurd than even the wildest of Hawks screwballs. (What does Monkey Business have on five hundred monkeys in a tree being captured by a rocket powered net.) Game catching is merely another profession to depict with utmost seriousness, such happenings come with the job. This is because, as always, Hawks never acts above his material.

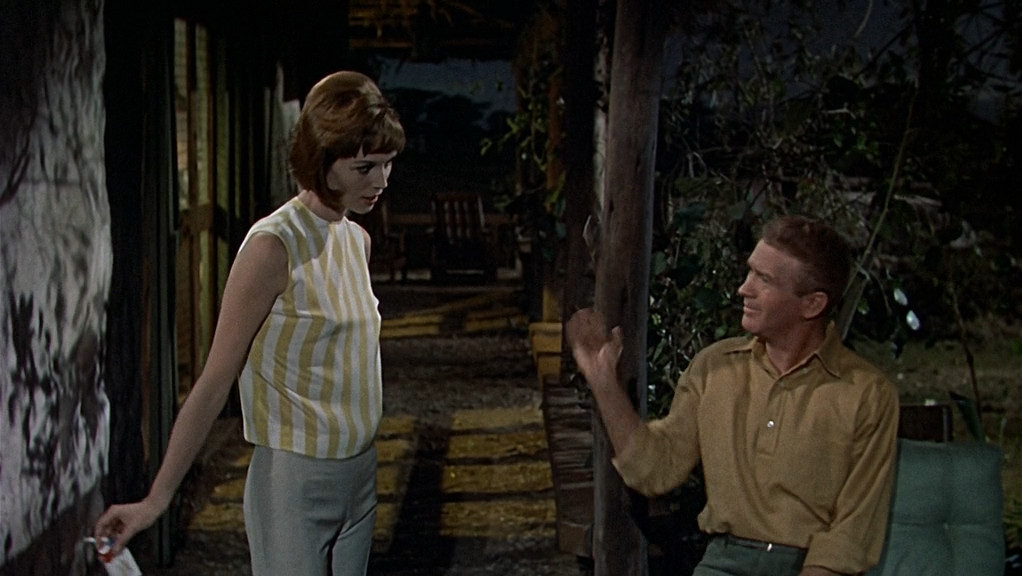

Hatari is the most Hawksian of Hawks films: full of his tropes, obviously without textual consciousness of them, all fully realized and done with swift nonchalance. This nonchalance is the genius of Hatari, watching Hatari is like being with a friend, and for a viewer who has seen many previous Hawks films, it is like reuniting with an old friend. One familiar with the movements of a Howard Hawks film will get the most out of it, it shows the most assured a filmmaker can be in relation to their material, direction is intuition, he is no different from the professionals of his own films. For a man who never considered himself an artist, what film is truer to life than a film in which the pan of a camera feels no different than the greeting of a friend?