Goodbye in the Mirror

24/07/2025

- Boomlight

24/07/2025

- Boomlight

Storm de Hirsch's Goodbye in the Mirror focuses on three girls: Maria, Berenice, and Ingrid, living abroad in Rome. While the film mostly centers on Maria, the New Yorker, it is modeled after their collective subjective gaze towards their environment. However, even if the film is working with their subjectivity, it does not remain complacent within it. If Goodbye in the Mirror is a film that sees Rome through the subjectivity of these girls, it is also one that challenges this perspective. One where the tourist’s idealistic gaze is forced into confrontation with itself.

Rome existed—and still exists—as a cultural hotspot, a spectacle of historical structures steeped in ancient mythology. The girls arrive with a culturally informed idealistic vision of Rome—an idealism that becomes subsumed into their gaze. They understand only the spectacle that Bazin describes:

"The Italian city, ancient or modern, is prodigiously photogenic. From antiquity, Italian city planning has remained theatrical and decorative. City life is a spectacle, a commedia dell’arte that the Italians stage for their own pleasure."This is in part encouraged by the Romans who take the girls sightseeing. They accentuate the girls’ reactions brought on by the structures, fulfilling their roles in sustaining the tourist economy. This idealism is even extended to the cinema of Rome. While sightseeing, Berenice points out the Spanish Steps, prompting Pepe, a film director, to exclaim, “That’s where we will shoot our new film! It will be a great film, with great actors—not black and white, in Technicolor!”

Berenice responds with her own naivety, saying,“When I become a famous film star, I’m going to buy this city!”

Goodbye in the Mirror uses its montage to transfigure space into pure subjectivity, and by doing so externalizes experience itself. When Maria, in the apartment, begins to simultaneously sing and play the guitar, the film cuts and moves between the complexities of her subjective experience. A distanced shot of the headstock is shown as she adjusts the strings and hums to find her key, and a shaky camera parallels her unsteady fingers as she twirls the string. When she begins playing, the film cuts to a distanced shot of her with the guitar, and the camera begins to zoom in—it is important that this is not a push-in but a zoom, which modulates the physical space around her. The camera moves shakily between her voice and fingers as they reach an equilibrium. Once she seems to become comfortable with what she is playing on guitar, the camera lingers on Maria’s face as she focuses on her voice, melodically singing "bum bum.” As she begins her song, the camera zooms out and, while zooming, angles itself slightly. Space begins to expand and transform as the distinct elements of the song find their balance. The film continues to cut around the intricacies of Maria’s playing until Ingrid enters the apartment. The film then shifts focus to Ingrid, and she is seen peeking around the door until the same distanced shot of the headstock is used again; this time reused to fit Ingrid’s gaze as she enters the apartment. Once Ingrid enters another room, the camera begins moving around her mouth and hand as she lights a cigarette, and, while the music is still being played, the film cuts back once again to the same distanced shot of the headstock, illustrating Ingrid’s relationship to the sound of the music.

Space is ever-changing and never an objective constant. When Maria and Federico, who has lived in Rome his entire life, are out walking, there is a distanced shot of them standing in front of the Pyramid of Cestius. Rather than a standard axial cut that pushes closer to the two’s conversation, the film instead reframes the space around them, exaggerating the pyramid’s scale in relation to the characters to further isolate their conversation, reflecting Maria’s gaze when conversing with Federico.

The two then enter into a dialogue:

—That’s not a castle; that’s Porta San Paolo, an old gateway to medieval Rome.

The film cuts to reframe Porta San Paolo as Federico describes.

But Maria refuses this gaze, and while walking away, says:

—Oh no, to me it’s a castle. I like to think that I’m living across the street from a castle, like when I lived in New York, I was only a block away from the Empire State Building: I could see it every time I looked out my window.

For Maria, she may as well be living next to a castle. To her, it is an Americanized preconception of the Old World that triumphs over reality.

Later on in the film, after Ingrid is kicked out of the apartment by Maria and decides to go on a walk, Rome is framed in a much different way.

Suddenly, what was once exciting and new is now dull. The Rome of ancient history and myth is now framed as desolate. Ingrid’s despair cuts through her naive gaze, providing another counterpoint to the girls’ initial excitement. The idealized Rome of before now appears shockingly modern, destabilizing the film’s initial romanticism.

Towards the end of the film, Federico confronts Maria after seeing her with another man, saying that he waited all night to ask for marriage. They seem to reconcile this issue, though this is not explicitly stated, only being shown through the almost-sweet face of Maria cut into a closeup of them holding hands.

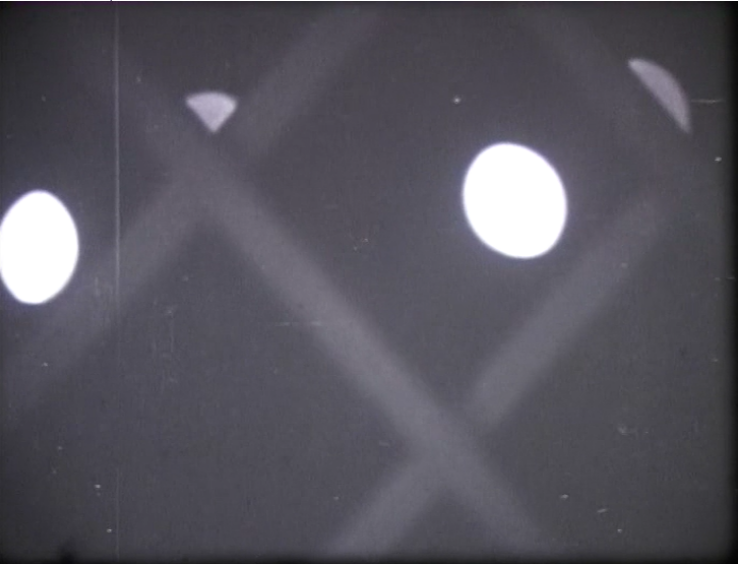

Maria instantly asks about plans to return to the States for marriage, which shocks Federico. “Maria, do you know what you are saying to me? I ask you to be my wife, and you already are shipping me off like a package to America. Back to America, I’ve never been to America.” For Maria can only see Rome through her displacement from America, and thus immediately assumes that Federico would be willing to “return” with her. Federico refuses, so she decides to leave Rome, and him with it. In the end, Maria’s subjective vision is reduced to an interior prison. In it, there is nothing but a barred-off blur of lights.

There is a deep anger and uncomfortability within Goodbye In The Mirror. De Hirsch, who, as Jonas Mekas described, was a “determined pixie woman” who “went to Rome, got mad, grabbed a camera, and made a feature-length movie,” found herself in line with her contemporaries of the NACG in constructing the film around a subjective, personal vision. But where Goodbye in the Mirror differs from films like Brakhage’s Dog Star Man or Menken’s Lights is in its lack of acceptance towards the isolating implications of the subjective gaze. Personal vision is not made sacred or mythologized, but rather laid bare in its troubling contradictions. While shooting in Rome and working with narrative, De Hirsch also found herself in between the Italian avant-garde scene and its internationalized mainstream. As such, the film becomes perceptive of the complacency inherent to a foreign idealistic relationship with Rome. Maria’s turmoil at the end of the film is exactly the dissolution of this idealism—the collapse of vision under the weight of its contradictions.