CINEMATECA PORTUGUESA-MUSEU DO CINEMA

MONIQUE RUTLER - “ISTO VAI MUDAR!”

50 YEARS OF APRIL: QUE FAREI EU COM ESTA ESPADA? | REVOLUTION

21 September 2024 - translation courtesy of Y. Z.

FRANCISCA

MONIQUE RUTLER - “ISTO VAI MUDAR!”

50 YEARS OF APRIL: QUE FAREI EU COM ESTA ESPADA? | REVOLUTION

21 September 2024 - translation courtesy of Y. Z.

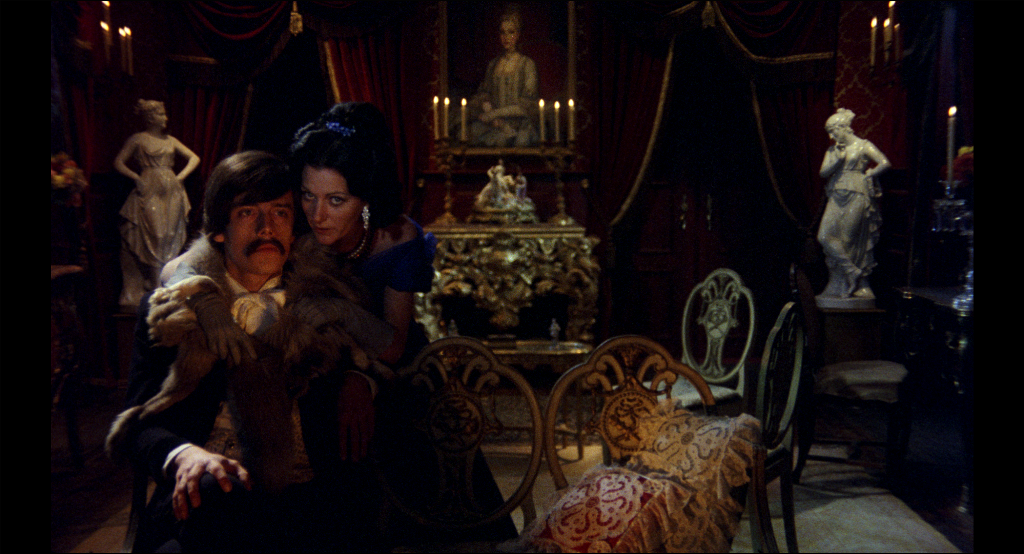

FRANCISCA

In 1999, when Oliveira premiered La Lettre/The Letter at the Cannes Festival, the Finnish historian and critic Peter Von Bagh wrote to me saying: “Of all the films that I saw at Cannes and it’s been 28 years that I’ve been going to Cannes (...) the new Oliveira was the greatest. More still: uniquely great, moving, profound - perhaps surpassing everything that has been done until today in the domain of reading literature cinematographically".

Oliveira liked this last formula a lot, finding that it made “the sum of the alternatives, seeing, showing and hearing”.

In fact, the cinematographic image isn’t to be read (like so many critics say so many times) but literature can be read cinematographically, through what Oliveira also called the “visual word”.

I deem that the first example of the “cinematographic reading of literature” or of the “visual word” can be found in Francisca, last panel of the so-called “tetralogy of frustrated loves”.

Oliveira has, for many years, underlined the importance of Benilde in his evolution. It was when he realized, in his own words, that “the cinema can only fixate”. But in Benilde he fixated a theater play and it is extremely different to adapt theater plays (as happened, with diverse approaches, in O Passado e o Presente and in Benilde, the two first panels of the tetralogy), than to adapt a novel as happened in the third panel, Amor de Perdição. In the theater, there are only dialogues or monologues, not in the novel. The question was to find equivalence for the word, for the literary text. Oliveira decided on an almost integral transcript of the Camilian text, entrusting on the “off” voices, which he called Delator and Providence, what the characters do not say. It was a radical solution, but a most difficult solution to contain continuity.

In Francisca, he never thought of integrally or substantially transposing Agustina’s novel, but he read it cinematographically, like he would afterwards with Vale Abraão, A Carta, O Princípio da Incerteza and Espelho Mágico. The essential - or what he judged as essential - is given by the images. Other pieces of information, necessary to the comprehension of the story, arise in intertitles, as in the times of the silent film. With an abyssal difference: in that time, intertitles were normally used to substitute dialogue. Now, the intertitles are adaptations of the Agustinian text, the dialogue are all Agustina’s, all cinematographically transposed from the pages of the novel Fanny Owen, published in 1979, for the film Francisca, filmed in 1980 and premiered in 1981.

The genesis of the book and film is curious and it is well worthwhile summarizing it. In 1978, Agustina was approached by the actress and director Linda Beringel and by the director João Roque, who wanted to make a film about Fanny Owen and asked her for the dialogues. Agustina wrote in the preface to the book: “To write the dialogues I had to get to know the circumstances that inspired them; and the story that bears them. Thus the book was born and I wrote it”.

“It seemed to me necessary and useful to bring Camilo Castelo Branco to the light of our human experience without translating it in the writer’s opinion which is mine. Because of this I used collage and almost all of his lines are the authentic ones, that he wrote, in novels, in the disperses and in the sheets in which he annotated his thoughts. Also many of Fanny’s and José Augusto’s words can be understood as heard directly from themselves in his life. In part, because like this it allowed them to be heard in the intimate dialogues; and also because Camilo fixated them in the books in which they posed as characters, still imbued with the passionate memory that immortalizes everything that it touches. Like this, perhaps everything may seem less evasive in this novel of evasions and of fascination that is the rule of interceptions”.

Regardless if they were shooting or if it was left, the film of Linda Beringel and João Roque never managed to be made and it was Manoel de Oliveira, fascinated by the evasions of this story, who decided to film it. The rule of interceptions continued.

Before continuing, it is fitting to recall that José Augusto Pinto de Magalhães and Fanny Owen (Francisca is the portuguesation of Fanny) were historical characters who Camilo knew well in 1849 (he was 24 years old) a year after having “disembarked” in Porto, coming from Vila Real, and having debuted as a successful writer. Success which also seemed to smile on José Augusto, in his incipient poetry. Both knew the Owen sisters at the same time, in 1850. They were the daughters of an English colonel, who was a counselor of D. Pedro IV during the siege of Porto, and who was not very fulfilling of conjugal duties, and of a Brazilian “who made a good impression on vulgar people”. The rest - which lasted only four years, seeing as Fanny died in August 1854 and José Augusto in September (they had married at the end of 1853 in this brilliant wedding at the Bom Jesus, where they are represented by two men) - not the tale that the book and the film tell. José Augusto was 23 years old, Fanny had not yet completed 20 and Camilo counted 34.

There is no novel of Camilo’s that is exclusively dedicated to the funereal love of Fanny and José Augusto. In 1858, Camilo narrated their story in the tale Sete de Junho de 1849, inserted in Duas Horas de Leitura. Agustina based herself on it and on various passages of later works. But neither Camilo, nor Agustina, nor Oliveira (nor, it seems, anyone) knew of the reasons that brought José Augusto to marry but not to consummate the marriage. Someone makes him receive letters that Fanny had written to a Spaniard. What would they have said? It isn’t known. It is known that it was him who ordered the autopsy of his wife’s corpse to find out if she was a virgin, as he had doubted previously and, after the certificate of this virginity (“Virgin as if she had never exited the lap of her mother!”) ordered her embalming and had her heart kept in a shrine that, for many years, has been in the chapel of the Quinta do Lodeiro, in the “sad house” of the Lodeiro. Would Camilo know of something more? Was it him who had woven the intrigue? These and many other hypotheses have been suggested, but neither in the book nor in the film can any explanation be found or is any thesis insinuated. As how no one ever knew if Benilde was a virgin or hysterical or whatever else, no one ever knew what happened between Fanny and José Augusto and of the reasons for the two’s tragic end. Frustrated love it certainly is. Why it was frustrated we don’t know, neither in the beginning nor in the end.

On the contrary to the book, the film starts with the reading of the letter that narrates the death of José Augusto. Afterwards it situates us seven years before, in a “climate of instability and despair”. José Augusto thought himself Byron and, at a ball, a masked woman “placed her hand on his chest and the camelia that he had on the lapel flaked off inside that hand”.

Afterwards, and after seeing glimpses of the love-hate relationship between José Augusto and Camilo, everyone finds themselves once again at a ball. It is at this ball that one of the sequences that best illustrates what Oliveira calls “visual word” is situated. It is the now famous dialogue between Camilo and Fanny. Camilo says to her that José Augusto is a funereal man and she asks why. “He doesn’t have a soul”, she hears as the response. But Fanny replies: “What is a soul? A butterfly also doesn’t have a soul and it knows how to touch the flowers like no one else”. Shortly after, Fanny says to him that “a soul is not a chair that one offers to a visitor. The soul is…”. There is a lot of silence and a lot of noise, simultaneously and not wanting to be paradoxical, Camilo wants to know more. “Is?” “Is a vice. The soul is a vice”.

Before Camilo says “My God” the figures return to the initial position and the dialogue repeats itself. After, the turmoil of the dance and the apparition of Raquel, at that time lover or ex-lover of José Augusto. It was the second time that Oliveira repeated a sequence (he had already done so with the death of Baltazar in Amor de Perdição) and this repetition fixates and fixates us. At that moment there is everything there is to know, there is everything there is to fixate.

Much later, already after the death of Fanny, Oliveira equally repeats the sequence at the chapel, next to the shrine with her heart, when José Augusto haunts the housemaid. Only that now this terrible and effulgent necrophilic sequence doesn’t repeat equally. We see (in close-up) José Augusto asking: “Do I scare you girl?” while he holds Fanny’s heart inside a jar on top of the altar and debits¹ his speech about viscera, about the heart and about love. After, the dialogue repeats itself with José Augusto in “off” and only the terrified housemaid in frame.

Oliveira said that if he were to use the shot-reverse-shot (which the sequence seemed to ask for) he would lose the sound of the background. “I wanted to provide her time and the housemaid’s time, the housemaid’s sensation, his sensation. Him talking to the housemaid - at this point he is talking to us - and afterwards our own reaction, reaction of the housemaid before José Augusto, until the housemaid runs away. I think that the second vision, that of the housemaid, is what best provides the phantasmagorical of the situation, the murkiness of the situation. It is the terror of the housemaid that really provides the perception of how much there is of funereal in all that. It isn’t in his apprehension, it is in the housemaid’s. And I wanted to provide all this at the same time, without cutting neither the shot of José Augusto nor the shot of the housemaid, without cutting either of the visions”.

It isn’t possible to be clearer in words and darker in visions.

Or it is. And it is impossible for me not to cite the sequence of Fanny’s death, with the feet outside of the sheets and José Augusto “in” and “off” the frame, after the fabulous conversation about “vulgar people” and after she asks: “wouldn’t there be a man who loves me?” Before she had spoken about her vision of vulgar women, “at the doors of little houses that they were like dovecotes”. And the last words are “Memory has gone with the soul”. It occurs to ask: had it gone with the vice?

In the old “folha da Cinemateca” about this film, M. S. Fonseca said that Francisca was the biggest work of Portuguese cinema. I don’t know if it is or not, thinking about other posterior films of Oliveira’s. But that it is an absolute masterpiece I am certainly sure. Reflections of a light that is only found once, as Agustina wrote quoting Plotinus, and as Oliveira filmed quoting himself.

João Bénard da Costa