The Cacique of Ireland

By Glauber Rocha

20th of July 2025 - translation courtesy of Victor Castro

By Glauber Rocha

20th of July 2025 - translation courtesy of Victor Castro

Rock Demers, former director of the Montreal Film Festival, was able to gather John Ford and Jean Renoir and Fritz Lang.

Ford arrived one week late, and with him came a terrible bad mood. The great director of Westerns—such as Stagecoach (1939), Fort Apache (1948) or The Searchers (1956)—is taller than Lang, older and blind in one eye: like Lang, wears an eye patch1. If Renoir is a tame lion, if Lang is a wounded tiger, John Ford is an aggressive hawk. Inaccessible at first glance, had his stardom demystified at the entrance of the hotel by Jean Renoir, who after seeing him shouted:

—Hi Fritz!

The French journalist Michel Ciment warned Renoir that it was not Lang, but Ford.

Smiling, Renoir answered:

—I know it, the confusion is intentional. I call Ford Fritz only to play with his vanity.

Ford walks to greet Renoir with a warm embrace. While going, however, he almost falls. He is weak, the man who once commanded the platoons, the buffalo herds, the warrior tribes. He coughs, but doesn’t give up cigars. While joking with Renoir, Michel Ciment took the opportunity to introduce me. Ford looked at me and screamed:

—Saudade!

I stood there, stunned by that folkloric “saudade”, pronounced so disastrously.

Ford hesitated some seconds and asked:

—Where is Raul?

—Which Raul?

—Roulien, Raul Roulien. My friend and great actor.

I gave the little information I had about Raul Roulien and Ford mumbled:

—Rio de Janeiro…

At that moment a priest appeared. Ford stopped the dialogue with Renoir and went to hug him. They talked for a few minutes. After that Michel Ciment told me that Ford was worried, because he needed to find someone to confess to during the Festival: an incorrigible Catholic, Ford goes to the church every day.

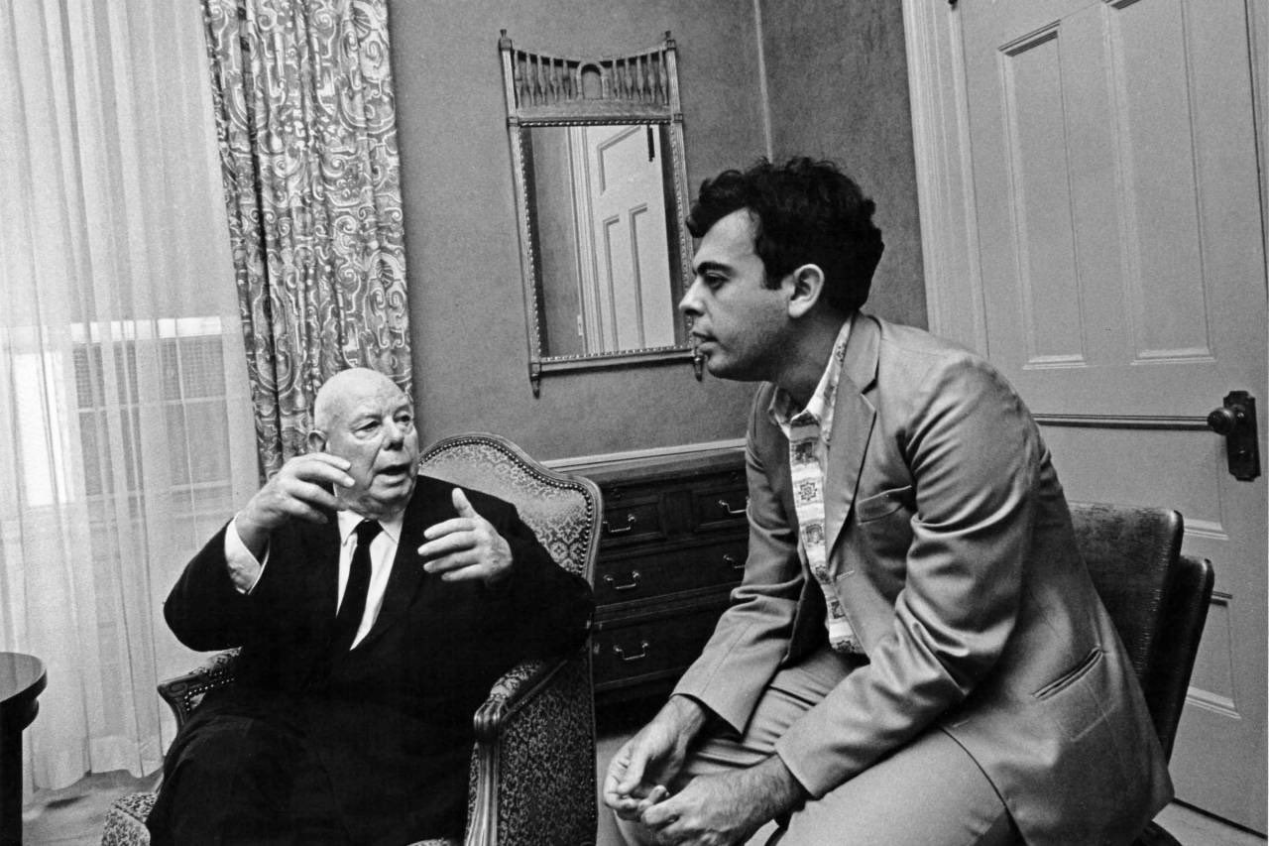

After so many mismatches, the meeting with journalists was made in the hotel room. Gin and Whiskey. Cigars. Wearing white shirts, tennis shoes, extremely tall, John Ford is what we can call an “elegant rude”. His gestures are like those of a Cowboy, even though he is Irish. It looks like after so many years dealing with cowboys, sheriffs, indians and bandits, Ford became influenced by his characters.

He has some of John Wayne’s mannerisms, screams when you least expect, looks like he is going to draw a pistol with every gesture.

The Festival, as a homage to him, decided to show his film Young Mr. Lincoln (1939)—A biography of the young years of the American Democratic patriarch.

When it was announced, Fords answered negatively:

—Which film? Young Mr. Lincoln? I don't remember it.

—It's a film with Henry Fonda—says Michel Ciment.

—Henry Fonda? But who is Henry Fonda?—asks Ford again, to the surprise of the journalists.

Ford is grumpy. As is known he is a Catholic, Democrat, conservative and an extreme anti-communist. Fonda is a Progressive. They had a fight once that also involved John Wayne, Ford’s intimate friend and member of right-wing terrorist organizations.

Ford, after that incident, started to ignore Henry Fonda. Now the legend is confirmed:

—If this film exists I don’t wanna watch it. I'm really tired and have serious problems at the moment. What bothers me the most is not being healthy enough to participate with the Marines in the Vietnam War.

A new surprise, Ford proclaims his alliance with the war and adds:

—I was visiting Howard Hawks while he filmed El Dorado (1967). Even though I don't watch Hawks’ films, I always visit him for a little game. Hawks said that he was going to make a film about Vietnam, which is a very funny war. Imagine our giant and equipped marines having trouble with those “little yellows”...—and only Ford laughs at his own inopportune joke.

Silence.

New questions come.

Speaking about the art of cinema:

—There's only one author in cinema: the banker from Madison Avenue. Nowadays I don't even choose the actors. It's the banker's woman that gives every advice on the film I'm going to make. Only when the film has my money in it can I have freedom. But which freedom? The public is the one in charge. If I make a film different from what the public wants, it's a failure, and you don't gamble with thousands of dollars. There's only one progress in cinema: technical. I was one of the creators of the Cinemascope, of the Panavision, of the Cinerama. Me and other colleagues.

About the new filmmakers:

—Who is Godard? Never heard of him. Who is Pasolini? Never heard of. Yesterday I went to watch a Yugoslav communist film (referring to Love Affair (1967) by Dusan Makavejev, loved by the critics) and I left in the middle of it. Is this cinema? Europeans think that filming a naked woman is cinema. The great cinema is ours, mine, Hawks’, Hitchcock’s!

The old man's petulance leaves everyone embarrassed.

One journalist takes a risk:

—Are you going to keep filming?

—I am more than eighty years old and I am not that old to quit. Right now I want to make another film and I have tons of scripts with me.

Suddenly, the hawk came to rest. Takes a sip of gin, smokes his cigar. He is away from there, maybe wondering beyond the canyons where he used to film Indian ambushes. Mumbles:

—I have to go back. My wife and daughter are sick.

One journalist asks if Ford will accompany Renoir that evening in the Festivals Palace, where La Marseillaise (1938) will be shown.

Ford grumbles:

—No. This film about the French Revolution is just propaganda. I can’t publicly honor a communist, even though Renoir is my friend.

Three days later Rock Demers sends a luxury Buick to bring John Ford to the cinema where Young Mr. Lincoln will be shown, and the cacique protested:

—Luxury cars are for Fritz, who’s so vain. I can take a cab.

But he goes in the Buick anyway. The same suit. When he arrives at the crowded cinema, an ovation. He raises his arms and asks for silence. Emotional, Fords shouts with a cowboy accent:

—In these moments we always say “this is the most important moment of our lives”... This is a simple film about a simple man made over twenty five years ago and I don't remember one single scene. The actors are unknown.

Young Mr. Lincoln begins. It's a film that left Eisenstein overwhelmed. We told that to Ford and he jokes:

—Who? Eisenstein? The communist director of Ivan, the Terrible? Ivan is a very intelligent film.

Young Mr. Lincoln, with Henry Fonda in one of the greatest roles of his career, is a nationalist and uncritical portrait of Abraham Lincoln’s predestined youth. All the data of the Fordian style are there: sense of humor, visual harmony, North American countryside folklore, humanism, religion, sentimentalism. The same Henry Fonda would come back in My Darling Clementine (1946), Grapes of Wrath (1940), Mister Roberts (1955) and so many other films made by the young Irish who began to shoot Westerns very early in Hollywood. In the skin of the Young Lincoln, Ford embodied the right and idealist American. We have the impression that it's a primitive document. When it ends, applause, not for the film but for Ford. He gets up and starts showing off the pride of a righteous man:

—You’re absolutely right to applaud. It's a beautiful film.

Laughs. The giant has tears in his eyes. He rarely had homages like that. In France, on one occasion when he was there, the critic Jean Mitry gave him a book as a present: his own biography. The old man was overwhelmed. Homages like that didn't exist in Hollywood, where he was only one of the studio employees.

Ford is skeptical about his possible genius. Undeniably a militarist man, Ford idealized the West as this lost paradise, a type of Olympus of the new world. His concern was always to punish the bad ones and make the good ones triumph.

He likes Indians, but they are naive savages who have to be catechized and protected. There will always be a good white soldier capable of such a feat, even if it means rebelling against his superior. The army is the soul of the nation, the cavalry always appears to save the poor colonies of the Indians' hands. About racism, Ford thinks the incomprehension between men is shameful.

His cinema created followers throughout the whole world. In France, Ford is venerated, even though everybody knows his vision of the world is unactualized, mainly after the United States started to enter into a social, economic, and political crisis, revealing to the world that his invincibility, vehemently proclaimed by the cinema is only a cinematographic myth. Like Howard Hawks, like Alfred Hitchcock, like many others, Ford belongs to a generation of giants that reveals themselves as Goliaths, vulnerable at the forehead.

Fritz Lang was right when he said that the cinema made by that generation was a primitive one. They invented fabulous scenes of spectacle, created genres and heroes, but contributed nothing to change society: only collaborated in the edification of the imperialist myth. This cinema of spectacle, of adventure, suspense, emotion, collapsed exactly because the time of the reflection, of the doubt, of the critic, of the perplexed, started. Today, in front of a film from the old American cinema, we watch only the fake reproduction of the world. And the perfection of those forms, the harmony of this rhythm, ends up getting tiring. It's a closed world that gives pre-digested messages to the spectator, without giving him a chance of disagreeing or to refuse.

John Ford is the greatest creator of this phase. Moralist, telluric, genius of an old style of spectacle, Ford was very well defined by the Portuguese filmmaker Paulo Rocha, while leaving from Young Mr. Lincoln:

—He is the last archaic poet of an electronic civilization.